Review: Rēwena and Rabbit Stew

Reviewed by David Veart

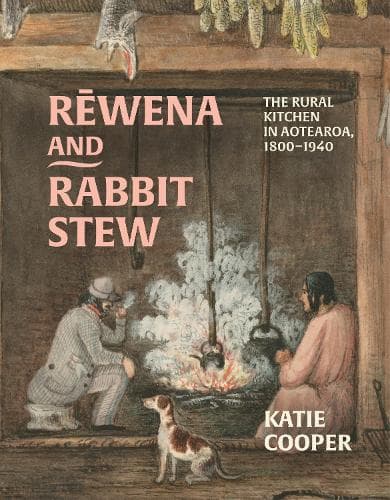

This book is an important milestone in the study of the foodways of Aotearoa New Zealand. In any food history there is a temptation to fall into a nostalgia tinged fantasy of what once was. Here author Katie Cooper instead creates a framework where memoir is combined with data to create a complex, nuanced description of how rural Aotearoa New Zealand, both Māori and Pākehā, lived and ate between 1800 and 1940.

We start in the ‘kitchen’, defined as ‘places with cooking facilities’. For Māori, tapu and noa are part of food preparation so this definition has added complexity. There is an image in the book, taken in the early 1900s of a group of Māori cooking, where they are outside and in the background is a kāuta, a cooking shelter. The area where the cooking is taking place is carefully fenced off from the surrounding wharepuni. Having excavated Māori cooking areas myself, parts of this look very familiar, with some simple scoops of burnt stones and earth, others hāngi many metres square. The pattern and continuity of behaviour connected to food preparation was very obvious at a site I worked on at Papāhīnu near Auckland Airport, a Te Akitai kāinga abandoned in 1863 when the population was expelled by government decree. Here the cooking areas were clearly separated from the whare with the hāngi, early in the sequence dug with traditional tools, and the final hāngi pits dug with spades. Technology changes while behaviour remains the same. By the time we saw all this the evidence consisted mostly of stains in the soil, but originally It must have looked very much like this image.

The new Pakehā arrivals had different rules associated with food and its preparation, although separation of cooking fires from the inflammable Māori built whare raupo or later timber cottages was a wise precaution. This book is filled with well chosen illustrations and one, a drawing by William Strutt, showing a settler on his roof desperately trying to extinguish his blazing chimney explains this problem eloquently. For some the risk meant that, as with Māori, cooking was done in a separate structure to guard against this eventuality.

One of the great strengths of this book is how Māori histories run throughout the narrative. For example the effect of legislation on Māori is a continuing theme. A powerful example is how the Maori Councils Act of 1900 changed the way Māori lived and cooked and how this was encouraged by Maui Pomare, head of the Māori section of the Department of Public Health.

Another Māori theme that links many parts of this book is the part played by manaakitanga in rural Aotearoa New Zealand. The provision of hospitality occurs in many Pākehā memoirs of rural life in this period and the Māori equivalent is well attested with manaakitanga encompassing a broader concept. The author quotes Hirini Moko Mead’s definition, ‘nurturing relationships, looking after people and being very careful about how others are treated.’ There are numerous memories from Māori of being instructed in the subtleties of manaakitanga. One which resonated with me is from Te Onehau Phillis who grew up in Te Teko. She recalls how they were never to clean up, ‘not even to whip away an empty plate’ until the guests had left the dining room.

For Pākehā women, especially those from urban backgrounds the expectations of rural hospitality, especially when it involved feeding unannounced dinner guests, took time to learn. Pamela Harrington from Te Awamutu recalls that to make the grade you needed to be able to take anything in your stride or be forever considered a ‘city girl at heart.’

The rural women describe hard work with a streak of stoicism. One woman writing to the Dairy Exporter magazine in 1927 talked of the need for optimism and that, in her relationship with her husband , it is ‘Mum’s part to help cheer him up.’ Another woman described her dislike of twice weekly baking days in a hot kitchen and thought that ‘...Paradise...would be a wee house somewhere with a bun shop round the corner.’ Baking a single perfect cake for a dinner party is very different to baking for your family, the fencers, a shearing gang, the haymakers and unexpected guests week after week.

The book examines the many parts of the rural kitchen, the technology, the move from outdoor cooking and open fires to solid fuel stoves and finally the electric range. The latter appliance has the added advantage that the kitchen in summer was no longer like an oven itself. Provisioning, where did the food come from? This chapter is comprehensive. From Māori origins all possible sources of food supplies are described, hunting, fishing, gathering, small farms, large farms, gift exchange, grocers, butchers and bakers. All this examined against a changing cultural and legal attitudes toward land and resources.

The stories told in this book are much broader than the title would suggest and much of the behaviour described has implications for later periods as well. Food histories often concentrate on what was being cooked, here the emphasis is on the person doing the cooking and the social framework within which the cooking took place. The kitchen is often considered as the centre of the home, but this book places it in the centre of very much more.

Reviewed by David Veart