Review: The Birds Began to Sing

Reviewed by primoz2500

It’s tempting to think that New Zealand music education is like a 1950s movie set in medieval England. I imagine a small huddle of plucky villagers inside the stone walls of a threatened castle, the enemy commentators edging ever nearer, siege engines poised, while beleaguered teachers prepare meagre defences against the terrifying battle-cries of the approaching army.

“What practical value does music have?!” the mindless attackers holler from atop their armour-clad stallions.

“Won’t someone think of the STEM?!”

And, most damningly, “Can my child make a career from this?!”

There are no knights in shining armour.

In response to this onslaught, educators are forced to make the case for music’s utility: music grants people life skills they will carry forever. It teaches young people to work with others. It forges neural pathways that are great for learning new languages.

I’ve used some of these arguments myself. I bought my godson a book called This is Your Brain On Music. Rather, I bought it for my godson’s arts-sceptic, computer programmer father. The young lad is now a proficient – on his way to fine – flautist and saxophonist. The thing is, though, no child picks up a saxophone because it’s good for them or because it will help them learn Danish.

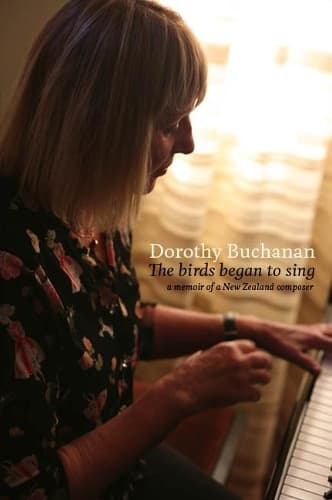

Dorothy Buchanan (b.1945) understands this. She also knows – in answer to that final, damning question – how to make a career from music. For many years a professional violinist, pianist and (occasional) singer, Buchanan is also one of our leading composers.

While she has perhaps been overshadowed by more avant-garde figures such as John Elmsly (b.1952) in Auckland and Jack Body (1944-2015) in Wellington, Buchanan’s vocal work Peace Song is none the less among the most performed compositions to have been written by a New Zealander.

Additionally, she founded her own music publishing company, sat on various QEII arts council panels and was one of the directors of the Women’s Composing Festival. Arguably, Buchanan’s greatest contribution has been as a forward-thinking educator. In 2001 she received an ONZM for services to music – take that, circling barbarians.

Impressive as all this is, none of these bare facts explain why a young person would pick up a saxophone. Early on in Buchanan’s new memoir, The Birds Began to Sing, she manages to distil that essence. Thanks to one of her teachers – and a small amount of chocolate – Buchanan learns at a young age that music is magic.

From that point on, she devotes herself to a musical life, never losing that early sense of enchantment, and clearly able to transfer a similar feeling to her students.

The Birds Began to Sing doesn’t quite manage the same feat. A forthright Catholic South Islander, Buchanan doesn’t go much for self-analysis. Useful descriptions of her music come from others, notably in snippets of reviews by Lindis Taylor (“imaginative, unpretentious”) and her musical mentor, the composer John Ritchie (“simplicity ... clarity and harmonic warmth. Not for her the modernism and so-called postmodernism of fashionable academe”).

Similarly, it is through others that Buchanan’s personality is best shown. In her own voice, Buchanan clearly adores her own family but often comes across as severe and entirely unforgiving of people – particularly teachers and musicians – she does not respect. Christchurch Youth Orchestra’s Peter Zwartz, for example, she claims was “a pretty nasty conductor,” while one violin teacher, “left a lot to be desired.”

A reprinted section from a Dominion Post interview with the author Kate De Goldi, however, reveals a different Buchanan, the one blessed with magical powers. Here the musician is described as “the most charismatic person I’d met,” and someone with a gift for reaching young people: “she’s not patronising at all. She’s playful.”

The Birds Began to Sing would have benefitted from more writing of De Goldi’s quality. Produced with Buchanan’s friend Lindsay Mitchell, the book reads as if it’s a transcribed interview. The reliance on Buchanan’s memory means a few factual errors have crept in.

Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra didn’t have a principal timpanist called ‘Lennie Bernstein’ in 2000, for example; Buchanan likely means percussionist Lenny Sakofsky. No big deal but simple enough to have avoided.

More frustrating, Buchanan jumps from thought to thought. Many conversations between friends do, of course, but in a book it makes for some bizarre juxtapositions. Within a few paragraphs Buchanan goes from her father’s ban on discussing the Springbok tour to moving house to writing music that accompanies a theatre work about New Zealand’s road toll.

This lack of focus curtails Buchanan when she’s at her most interesting, such as describing her musical process or, beautifully, her love of teaching – the magical bits. These are things Mitchell might have teased out, rather than allow to be cut off as Buchanan drifts to another subject.

The Birds Began to Sing nevertheless contains some fascinating information - Buchanan was briefly taught by James Joyce’s sister, who was a nun in the South Island, for example - and there’s the clear sense of someone fully embedded in the artistic life of both Christchurch and Wellington, appearing to have known anyone who’s anyone in the arts world.

Best of all, she doesn’t bother arguing that you should learn music because it’s good for you. Even now, in retirement, Buchanan shows herself unwilling to surrender to the barbarians. She doesn’t need the knights; she knows how to conjure magic.

Reviewed by Richard Betts

Read the first chapter here https://www.ketebooks.co.nz/all-book-reviews/2021-first-chapters-the-birds-began-to-sing-a-memoir-of-a-new-zealand-composer-nf247