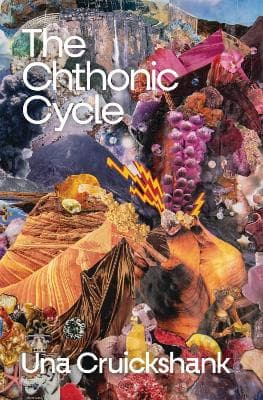

Review: The Chthonic Cycle, by Una Cruickshank

Reviewed by Kelly Ana Morey

‘People everywhere have always wanted to know the future, or so they think, and have devised a variety of tools and techniques to read it. We’ve read prophecies in heated jet on axe blades, in pyritised ammonites, in entrails and economics. But we don’t need magic to see the future. It’s easy to read it in the past.’

The Chthonic Cycle is a collection of the most marvellous essays. A veritable Alice in Wonderland trip down the rabbit hole of writer Una Cruickshank ’s incredible mind and the magical, mystical research adventures it takes her on, and the reader with her. Because of my own eclectic interests, passions and research journeys, being taken on someone else’s beautifully curated, eclectically researched and elegantly articulated jaunt around an eccentric collection of subjects, precisely stitched together as an encompassing whole, is exactly what I want from a collection of essays. The overall exegesis of The Chthonic Cycle is the endless carbon cycle of death and decay beneath the ground, the chthonic of the book’s title, and the flip side of the card, reincarnation, rebirth, reanimation and re-emergence into the world of light. Each of the essays has their own story to tell, about an extraordinary wide range of subjects - from a religious sect in the late-18th/ early-19th century in rural New York State, to coral reef polyps, the Great Exhibition, electricity and ergot poisoning, to the burning of the deceased on the banks of the Ganges, but they still string together, irrevocably linked in many different ways to Cruickshank’s thesis.

‘It’s the fate of everything on Earth,’ writes Cruickshank, ‘to be dismembered and reconfigured over and over. Only the intricate whole persists, a system that runs on interlocking cycles of death and reuse, like a set of ivory puzzle balls.’

Not only is Cruickshank’s subject matter a cherry pick of deliciousness, but her writing is fantastic, speaking to the time she has put into this book. Has filling up the car ever been more poetically realised than ‘every litre of petrol pumped into a car is a distillate of extinctions’? Or who would have thought that the coral polyp could be a profound mediation on what it is to be human, as per the quote below? It sings with the sheer pleasure of words placed to delight.

‘The overwhelming bulk of a coral colony, all but a few centimetres of living tissue at the top, is made of dead polyps. This is the wonderful, horrible origin of coral. It’s all corpses. A coral reef is a city of tiny bones, one that can stretch hundreds or thousands of kilometres... Polyps are a kind of anti-hero of the sea, who don’t intend to do good but incidentally benefit everyone simply by enacting their strange, vicious, comical life cycle. Their unthinkably ancient pattern of spawning and cloning, killing and feeding, until it’s time to die and become part of a bone labyrinth, is both a horror and a wonder.’

It's all written with a poet’s sensibility and a hard arse researcher’s passion for the facts. There are incalculable hours of research on these pages, not to get to the end, but simply to go on the journey. The essay ‘Jet’, for example, traverses the creation of jet from a tree falling and the painfully slow carbonisation that happens for millennia beneath the ground, to Whitby which is jet central in Britain, and then onto Victorian mourning practises, the industrial revolution, fossil fuel mining and reincarnation. Jet itself guest stars in other essays, a type of cross-pollination that occurs regularly throughout the collection.

Another example of Cruickshank’s love of unending cycles is a ‘A Little Spark May Yet Remain’ which begins with the resuscitation of drowning victims from the Thames during the Georgian period by various means, including electrical shock. It then takes the reader on a brief, elegant history of electricity and the investigation of its claimed capabilities in reanimation. From there to body robbing from the gallows for medical schools and public dissections, then back again to electricity and experiments in reanimation. Much talked about and well attended demonstrations that inspired Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, still in her teens when she wrote Frankenstein, published when she was 20. This very neatly brings us back to the beginning of ‘A Little Spark May Yet Remain’ with Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s mother, in despair from being spurned by a lover, throwing herself off the Putney Bridge and into the Thames and being brought back to life after being hauled from the drink. If she had been successful in drowning herself there would have been no Frankenstein as Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley wouldn’t be born for two more years after this, her mother’s second suicide attempt.

The Chthonic Cycle appropriately ends where it began with the cremation smoke from the bodies beside the Ganges curling up into the sky as pure carbon ripe for reincarnation on a molecular level.

‘Much later,’ concludes Cruickshank, ‘you’ll realise that the single lesson of your first cremation was this: that death punches a small hole in the fabric of ordinary life, and whether it lets solemnity in or frivolity out is uncertain. Maybe the traffic goes both ways, like the boats on the river and the people on the ghat and the cars on the road above.’