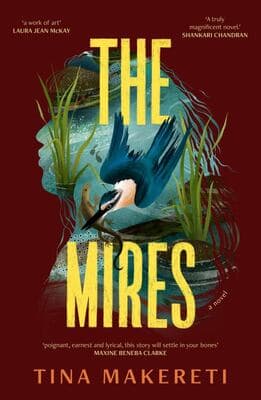

Review: The Mires, by Tina Makereti

Reviewed by Natasha Lampard

Let us start at the beginning - which is wai, which is water. Wai is our health, our waiora. It is our songs: waiata; our stars: waitī, waitā; and it is our fundamental essence and connection to whakapapa, whenua and realms of te ao: our wairua. To say, ko wai koe is to ask, who are you? To say, ko wai koe is to affirm you are water. Wai is thus both the question and the answer, a fundamental element of the world around and within us. And wai is the fundamental essence of The Mires, the latest pukapuka by acclaimed author Tina Makereti (Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Te Ati Awa, Ngāti Rangatahi-Matakore and Pākehā).

A haerenga into a world that speaks to past as present as future, The Mires is set in a post-lockdown, not-too-distant time - a wā that could conceivably be any day from now. It deftly weaves the threads of whānau, connection, dominion, class, race and gender. Insidious erasure and convenient amnesia of history (of a nation, a family, an individual) is considered carefully, as is precarity - financial and otherwise. The instability feels acute: the relentless vigilance, the ever-present exhaustion. It is a story of what it means to be at home: in this world, on this body of land, this body of water. And what it means to be at home in ourselves.

The Mires centres around four mothers, three of whom are neighbours in a small block of council flats in Kāpiti, on land that was once wai, a source of fresh kai and a connection to other waterways, other pā, other people. Connections for the most part now gone and forgotten.

Keri is a single mother of four-year Walty and teenage Wai. She has returned to Aotearoa after years in Australia, escaping the violence of an abusive partner. Her daughter Wai, has what some call “the knowing” - matakite. She sees and feels the vastness, the immense and the infinitesimal, of the world and of that within it. Wai “lives somewhere just beyond reach”, and is, like the waters she knows so intimately, an embodiment of both calm oasis, and turbulence.

Next door lives Sera, with her husband Adam and their daughter Aliana. New to Aotearoa, they are refugees from a place unspecified, having escaped a different kind of violence, that of environmental destruction. While Adam adjusts quickly and with excitement to their new life, Sera, tightly wound for so long by necessity,, so focused on mere survival, now is unravelling.

And then there’s Janet, Mrs B. A Nell Mangel-like figure of the curtain-twitching variety, all caucasity and audacity. Keri describes her as “prejudiced but alright”, but in Janet, Wai observes “something discordant, a kind of sour note”. Having escaped her own circumstance of violence, Janet has more in common with her neighbours than she knows or seeks to discover. Her curiosity, it seems, often arises to formulate judgments of others, rather than to understand both them and herself. She’s wounded, and wounding.

Janet is mother to Connor, who is trying to treat his feelings of inadequacy, of disconnect, with a potent blend of white supremacy. He is ‘trying to figure out how to make an impact, how to prove himself…to make out as one of the clever ones’ and offers a disquieting study in how and where and why extremism and a fluency in cruelty develops.

The fourth mother depicted is Swamp mother, the voice of the repo, the primordial waters of the mire, who acts as a carrier of the story, and a meeting point of the various narrative tributaries. She is a voice of eons, of wisdom, and of insistent memory, not unlike the author herself.

In different hands, the story could have been didactic. But Makereti skillfully navigates complex waters and offers both a meditation and a provocation on identity and belonging and relationships, and on our conception of what is fixed and what is unstable, and how quickly, how easily, the ground beneath us - physical or metaphorical - can fall away. It speaks to acts of care, and dignity - the ways in which we (both people and institutions) uphold or diminish it, of how we respond to indignities, and to feelings of isolation. As both Keri and Sera encounter systems of bureaucracy, the story highlights the many and varied indignities-by-design, as well as the etymological paradox of the very words used to describe their functions. Welfare: to help one to fare well. Benefit: the root of which is "to do good" but which is so often maligned. Refugees: people seeking refuge - but whom some seem to think we need a haven from, rather than to give a haven to. (How frequently we use words meaning one thing, to describe its very opposite.)

With Makereti’s signature elegance, the characters and the story are vividly rendered, wholly immersive. To read The Mires is to feel it, it is bodily, a story that looks outward, but is experienced as something keenly internal. The writing is both silken, and splintering - working its way inside you. It can be an anxious read: I felt the raru brewing in my waters; I had to remind myself to breathe. But that is the point. The discomfort speaks to the disconnection - from whenua as both land and placenta, from that from nourishes and gives us life. It speaks to our need for rematriation to our taiao and thus, to ourselves and each other. In the erasure of the many waterways - in Kāpiti and elsewhere - points of human connection and places of community were lost. The forging of friendship between, for example, Keri and Sera, arising from the friendship between their children, Aliana and Walty, acts as a welcome counter.

Makereti gives us a story of tension and tenderness, of magic and meaning, steeped in grace, and timeless wisdom. So often in the reading, I heard the whisper of the great rangatira Moana Jackson beckoning us to consider our part in the creation and maintenance of “a place to which we can all belong, a place upon which we can all stand”. So often, I felt as if he was in the room with the author when this story was written.

The author said of literature, that it, “can do two things. It can give us a home, a safe place; and it can take us as far away as we want to go, expanding our world beyond what we knew was possible.” In The Mires, Makereti does that and more. It is a karanga, and a wero. It is a reminder of the insistent truth that our humanity and our flourishing, lies not in dominion, but in kaitiakitanga, manaakitanga and community; in interconnection with and care for our bodies of water, our bodies of land, and for each other.

I mihi to the author for this taonga.

Reviewed by Natasha Lampard