Review: Toi Te Mana: An Indigenous History of Māori Art, by Deidre Brown and Ngarino Ellis, with Jonathan Mane-Wheoki

Reviewed by Jade Kake

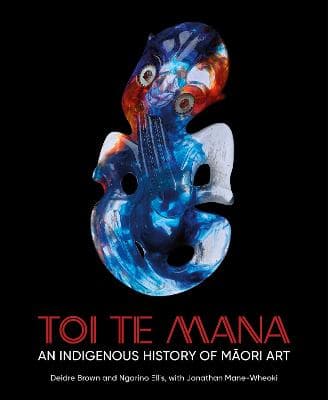

At a little over 4kg, Toi te Mana is a hefty tome, weighing as much as a healthy newborn baby. Unsurprising, perhaps, given this taonga is the culmination of 12 years of scholarship by two of our foremost Māori art historians — Dr Deidre Brown (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahu) and Dr Ngarino Ellis (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Porou) — with the book’s third author, Jonathan Mane-Wheoki (Ngāpuhi, Te Aupōuri, Ngāti Kurī), passing away two years into the project. The book is a scholastic visual feast: richly illustrated, thoroughly researched, and impeccably referenced.

This book presents a very nearly definitive history of Māori art, which is no mean feat. Of course, it’s inevitable that someone will be left out, and a book is only ever current the moment it is published (which, in this case, is a wonderful problem to have, bringing with it the need for more critical writing and more publications by Māori scholars). The work focuses on art movements and material culture, rather than individual artists (although a number are profiled). Or, to use a mathematics metaphor: Picture a line. This line (an asymptote) represents a definitive Indigenous history of Māori art. Picture a curve that almost (but never quite) touches the line. That curve is Toi te Mana.

The book is critical, disrupting ideas of progressivism and history as chronology, thoughtfully interrogating art history as a discipline and questioning its inherent Eurocentrism. In its place is presented a Māori conception of art history, grounded in Māori ideals, concepts and theory. It draws on queer theory, feminist theory, and postcolonial theory, including an interrogation of the term ‘postcolonial’ that posits the formation of a sense of global Indigenous solidarity whilst simultaneously questioning the idea of global art conceived through the Western gaze. The queer and feminist lens particularly bears mention, the authors unpacking inherently colonial views of ‘traditional’ Māori art and customs, exposing the inherent distortion of our practices by colonisation, even as our tūpuna sought to adapt and repeatedly demonstrated their agency and capacity for innovation in a rapidly changing world.

Traditional Māori literary forms are used liberally throughout, prioritising a Māori worldview. These include, whakataukī, mōteatea, and karakia. A favourite – 'Ko te tohu o te rangatira he pātaka whakairo e tū ana i roto i te pā tūwatawata' or, 'The sign of a chief is a pātaka that stands in the fortified settlement' (‘Pataka: the Maori treasure houses’, Te Ao Hou, no. 40, September 1962, p.32., cited in Toi Te Mana, p. 52). For scholars and those wanting to follow their own curiosity and the paper trail back to primary sources, the authors have shown us the way. The book makes extensive use of primary sources, and these are all carefully referenced, including early anthropological texts, Māori language newspapers, and the diaries and letters of early missionaries.

Ngā kete e toru o te mātauranga, the three baskets of knowledge, are used to structure the book, and to loosely divide Māori art into three separate, but connected and overlapping, categories. The pūrākau of Tāne and the three baskets of knowledge is here used as a structuring device, deliberately preferencing Māori forms of knowing over more Eurocentric devices such as chronology or media. The grouping is thematic; it may be read as broadly chronological, but the journey itself is non-linear. The book evades outdated categories of traditional and contemporary, instead asserting that customary art is contemporary art.

For those unfamiliar with the story, in one tradition, Tāne travelled to the heavens to seek the three baskets of knowledge (in others, the protagonist is Tāwhaki). Versions vary, but broadly, the three kete relate to three categories of knowledge. Te kete tuatea contained customary knowledge, and includes makutu, war, agriculture, carving and woodwork, stonework, and earth work. Te kete tuauri contained knowledge of the natural world, sense perception, and prayer. Te kete aronui contained knowledge of arts and crafts beneficial to humans, including maramataka, ritual, and philosophy.

Toi te Mana reinterprets and reimagines these categories of knowledge, creating a new system of categorisation of epochs of Māori art that resists a strictly chronological ordering. On definitions and scope: Māori art is defined, unequivocally, as art made by Māori. Art is a slipperier term to define but is here considered in the broadest sense of the word, encompassing Māori material culture in its entirety. Social art and the art of political movements are considered within this wide definition. Only performing arts is excluded (but that may be a topic for another volume).

Within the pages of Toi Te Mana, te kete tuatea, the first kete, covers customary arts, including carving, weaving, architecture, waka building, and adornment. The book engages in a continuous dialogue with our origins in Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa, reflexively referring to whakapapa and artforms at the point of origin to explain the adaptation of our artforms to a new climate and geography. Architecture is seen as foundational, rather than adjacent to, Māori arts, and the foundation established through the first section firmly establishes arts as permeating all aspects of Māori life, culture and customs. Likewise, Toi te Mana refuses to relegate Māori art to cultural anthropology, instead art history, architecture and anthropology are seen as inherently intertwined and ultimately inseparable.

Te kete tuauri, the second kete, describes the changing Māori artforms as a result of colonisation and early cross-cultural exchanges, and includes religious art and architecture, the arts associated with the social practices of utu (or reciprocal exchange) and tatau pounamu (peacemaking), the impact of new materials on customary art forms, tā moko finding a new expression as signatures on paper, socio-political arts, including how these manifest as architecture, and the often-fraught relationship between taonga and museums. In this section, a different type of adaptation is explored, this time in the face of rapid social, cultural, technological and political change.

Te kete aronui, the third kete, explores the art of social reform, led by Te Puea Herangi, Tā Apirana Ngata and others, and how this manifested in art and architecture post-World War I. This section also covers the art and architecture of the Māori prophet movements (particularly, the Rātana movement). The development of Māori urban identity and its manifestation through art and architecture post-World War II is also documented. The emergence of contemporary Māori art is charted from the 1950s onwards, with Māori artists trained in non-Māori artforms producing a diverse range of work in a range of media, including photography, video, painting, mural and street art, sculpture, and installation arts. The relationship between Māori and art galleries and institutions is explored, with Māori curatorship and art writing emerging as distinct disciplines in the 1990s.

In this section, too, contemporary Māori architects and designers are showcased. Tikanga is prioritised over motifs, materials and form and is positioned as the basis for practice, with contemporary Māori designers pushing back on the appropriate of Māori artforms and motifs by non-Māori designers, unapologetically taking up space and reclaiming ownership of our taonga tuku iho – and their contemporary manifestations. Finally, the journey then takes us to Australia, London and beyond, charting the rise of Māori art in diaspora, and in the rise of high-profile Aotearoa-based artists exhibiting on the world stage.

Three cross-cutting themes emerge: whenua, tikanga, and whakapapa. These are summarised in the kōrero whakamutunga (conclusion) but are evident throughout. These generative themes, again, prioritise a Māori worldview, and are central to understanding Māori art: across media, across time, and irrespective of geographic locale. An understanding of these themes is critical to understanding the movement of Māori art through time. I hesitate to call this ‘development’ (rejecting, as the book’s authors have done, the ideas of progressivism and history as chronology) and instead I will use the word ‘adaptation’ to describe the changes witnessed and the trajectory of Māori art through time. I am reminded of the whakataukī 'Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua'.

Toi te Mana is a serious scholarly text, an engaging (and somewhat intimidating read – it’s huge), and a major contribution from two of our foremost thinkers. If you have even a passing interest in Māori art (conceptualised here in its broadest possible sense), Toi Te Mana deserves a place in your bookshelf or on your coffee table. A remarkable achievement.

Reviewed by Jade Kake