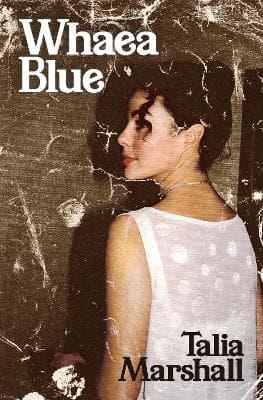

Review: Whaea Blue, by Talia Marshall

Reviewed by Jade Kake

Whaea Blue, the debut nonfiction release by Dunedin-based author Talia Marshall, is difficult to pin down, the format and genre eluding neat categorisation.

Marshall (Ngāti Kuia, Rangitāne o Wairau, Ngāti Rārua, Ngāti Takihiku) uses self and her lived experience to explore broader themes, including colonisation, race and racism, iwi, hapū and whānau specific histories, and experiences of mental illness. It’s a kind of autofiction more akin to the personal essay, expanded into book form, and could be loosely described as creative nonfiction.

“The personal is political”, that famous slogan of second-wave feminism is embodied within the book's pages, Marshall’s life and personal experiences forming the backdrop and site for deeper analysis of broader political and societal issues. Which might sound dry, but rest assured, Whaea Blue is anything but. She braids together the whole, and what could easily fall apart (the structure is a loose, open weave at best) instead holds together and pulls the reader forward.

Encapsulated within the wider narrative, there are essays on Mormonism in Aotearoa, Ans Westra’s photography, the musket wars in Te Tau Ihu, her tūpuna Nicola Sciascia (and his and Riria’s many descendants), and the complicated legacy of Te Rauparaha. Marshall reveals things that might be better left unsaid, leaving no stone unturned. She is self-reflexive within the pages, noting the ways in which Pākehā might twist these truths against us but remaining determined to present these within context.

The book is full of tohu, and kēhua, and tohu immersed in dreams. Marshall is a prophet, and I follow her signs, individual episodes slotting together into an increasing cohesive whole as the story unfolds. When her tūpuna visit her i te pō and whisper to her in te reo, I’m reminded of when three of my tūpuna whaea visited me in my kuia’s home the night before the commemorations for our tūpuna tāne, and whispered to me in a language I couldn’t yet understand in a hissing cadence, low and urgent. As Māori, we’re always looking for the signs, finding patterns in the unexplained and unexplainable. He Māori ahau, nā konā, ka mātakitaki au i ngā tohu.

The book includes the use of te reo Māori throughout, a feature common to much writing in English by Māori (in particular, but not exclusively) in Aotearoa New Zealand. Marshall uses rich, allegorical language, steeped in metaphor. Much of the book reads like te reo Māori transposed into English, with the structures and features of our reo, our worldview and our thinking pushed through the prism of our new tongue. She speaks on the limitations of using English to reach into the past, the limits of our colonised imagination and our colonisers' language on our tongues, our shared whakapapa inextricably intertwined.

The story moves in and out of realist and surrealist fiction like a fever dream. My favourite part of the book is a sequence where Ans Westra and Hone Tuwhare share a kai of mussels and kōura by the fire, and Ans performs endlessly for a cruise ship of the dead. The scene is dark and unsettling, and a rising sense of unease crept up on me as I read that section.

Marshall repeatedly tells us that she is an unreliable narrator. The personal relationships depicted in the book span the near totality of human existence and include her Pākehā Mormon grandparents, her radical lesbian mum, her estranged father, her son, her son’s father, other partners and lovers, her tūpuna (known and unknown), other women that are close to her like sisters, including her son’s aunties. She is unflinching in her retelling of abusive and troubled relationships with men, and she doesn’t gloss over the details or the residue of her trauma that reverberates through the story like an echo.

This book was a wild ride. I’m still trying to pin down my thoughts, which remain slippery, the story soaking through me and permeating through my skin. It will linger with you, like the stench of cigarette smoke on your clothes. All I can do is recommend you jump on board and hold on tight.

Reviewed by Jade Kake