Review: Roderick Finlayson: A Man From Another Time

It's almost inevitable that the biography of a committed writer becomes a narrative of desk, bent head, queue of titles. It happens here sometimes but Hickin quickens the story with his sympathy, nicely judged balance of life and literature, and his own anecdotal skills.

A couple of years back, I reviewed a Roger Hickin-edited anthology, also from Lyttleton's sturdy Cold Hub Press, of the late Roderick Finlayson's fiction, verse, essays and a few other literary forms. I praised its judiciousness, its success in showcasing a multi-skilled New Zealand author who was also a passionate, vital man, a courageous supporter of Māoritanga and tikanga. I suggested that the book could initiate a re-evaluation of Finlayson's status.

Hickin was already way ahead of me. The artist / poet / translator / designer (he's shaping to be as versatile as his subject) has now come out with this meticulous, engaging biography. The sub-title? Hickin’s aim is to show Finlayson in the context of his own decades, to indicate how his attitudes to race, gender, politics, national identity reflect the early to middle decades of last century. It's not meant as a literary bio, though it does give nimble summaries of Finlayson’s work, plus his development as stylist and narrator.

It draws frequently and pertinently on Finlayson's unpublished Scenes From a Writer's Several Lives (great title). Its research is almost breath-stopping: Hickin has found reviews for almost every Finlayson work ever published – and what a portentous little prat I sounded in the 1970s....

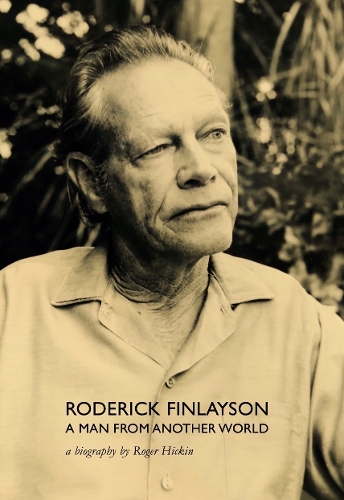

There are 30-plus pages of notes, sources, index. There's a generous selection of photos and other images: book covers; Finlayson with new wife Ruth and subsequent family; portraits of Baxter, Sargeson, O E Middleton, Brasch, hardly any women writers except for Helen Shaw. Finlayson's own face is square, seamed, with a jaw you wouldn't want clenched against you. As often happens, the black-and-white shots have textures and outlines more dramatic than colour can provide.

So – the life. It starts almost melodramatically, with Finlayson's gambling-addicted father borrowing money, setting off to work from the Mt Eden family home, and detouring to the United States, from which he never returned. Toddler Rod and his mother move to relatives in teeming Ponsonby, a place of unsealed streets, Catholic-Protestant feuds, glimpses of four-masted ships in the harbour below and a multi-ethnic ambience which was to permeate nearly all the author's work.

Rod grows, goes to Seddon Tech, has to join the school cadets, is allowed to bring his .303 rifle home. (Pause here for exclamation marks.) A benign Irish police sergeant later saves him from prosecution for failing to attend Territorial Force parades. Yes, right from the start, there are episodes which could have come straight from Finlayson's fiction.

He stays multiple times on a relative's farm near Tāneatua; meets Māori shearers and the prophet Rua Kenana. More material for future work begins to build. “(P)erhaps I am mostly Māori and can play Pākehā only when I try hard,” he muses. There's a love affair with a young Māori woman, the abrupt ending of which troubles him for ever.

Adult responsibilities also start to build but not till he's travelled to Rarotonga, where he sees some of the recluses and runaways who will also appear in stories. He's beginning to sell articles to various periodicals, but marriage to 14-years-younger Ruth forces him into relatively regular employment, first as an architectural apprentice, then in the Town Clerk's Department of the Auckland City Council, a position almost too incongruous to use in fiction. The Finlayson whanau appear and grow; ultimately there'll be six children.

All the while, Rod is writing. The legendary Bob Lowry likes and prints some stories. (It took three decades for the first edition of 250 to sell.) The author starts to befriend other writers: tattered and exotic D'Arcy Cresswell, waspish but generous Frank Sargeson, Rex Fairburn, David Ballantyne. Almost forgotten names, some of them. He likes them, and they like him.

His profile grows. Brown Man's Burden, Sweet Beulah Land, Other Lovers: the story collections don't necessarily sell in big numbers, but they're acknowledged and admired, for their rich, respectful rendering of Māori as well as their literary skills. He tries a novel, full of his Rarotonga experience. It's called The Schooner Came to Atia. His literary peers rave over it. It's been out of print for half a century.

He's in the Home Guard during WWII; frets that his new collection may not get published “before the invaders arrive.” His marriage is contented, though he can be an absent father, wrapped up in his worlds of words. Ruth proves to be a dab hand with the TAB; her wins usefully supplement the family income. (The family are often short of money; how unthinkable for a writer.)

Rod supports OE Middleton in a libel case against the noxious weekly Truth, which claimed the other writer was a Communist subversive. The Finlayson family manage an overseas trip. Gradually, imperceptibly, Rod grows elderly. His friends begin to die.

He converts to Catholicism. It's startling, yet understandable, and Hickin explains it nicely. He and Ruth move to Weymouth, start a huge vege garden, watch the Auckland suburbs come crawling over the hills towards them. He's writing nearly all the time; is quietly pleased with what he's doing. He dies in 1992, aged 87, almost but not quite an elder literary statesman. From then until Hickin's admirable work, his reputation has receded.

It's almost inevitable that the biography of a committed writer becomes a narrative of desk, bent head, queue of titles. It happens here sometimes but Hickin quickens the story with his sympathy, nicely judged balance of life and literature, and his own anecdotal skills. Finlayson's voice is always there: modest, careful, quietly turning the everyday into the emblematic. I reckon he'd have nodded approvingly at Hickin's rendering.

Reviewed by David Hill