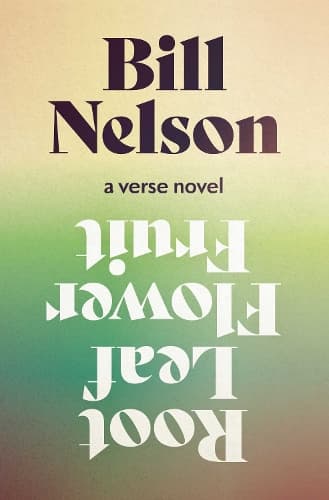

Review: Root Leaf Flower Fruit: a verse novel

Reviewed by Vaughan Rapatahana

I enjoyed reading this slim volume. Why? Not just because the plot momentum and machination transported me swiftly through the pages, augmented as they are by much of the script being written in unrhyming free verse, but because Nelson writes well, scribes skilfully. The book is easy to explore.

The verse aspect – given that the entire final section titled Fruit is not written as such, is speedy stream of consciousness sweeping not only the two main characters – grandmother and her grandson – but also the reader, ever onwards. The intelligent creative imagery is rather remarkable for the sheer number of similes saturating the text, for example, ‘no safety net, like walking the top of a fence like when she was a girl, arms out, toes pointed, like an Olympic gymnast.’ Indeed, the word ‘like’ is repeated inside a single paragraph in more than one instance, as for example on page 61 where we encounter ‘like the crack of a fresh sheet’ ‘like an iron maiden’ and ‘like bitter chocolate’ across eight lines.

And it is similitude that propels the plot too. The grandson, recovering from a bicycle smash-up, as well as a marriage that has matured away from spring romance, and a vocation he no longer finds favour or flavour in – both partly because of his accident - is already an Outsider figure, “working” alone at the top of a university tower. The grandmother has never fit in anywhere, even before the stroke that ultimately sends her to hospital and hospice care, and she refuses to submit to the strictures of Pākehā society whereby it is almost a given that fertiliser and pesticides should be employed on farms such as the one she and her remote husband acquired. She steadfastly refuses such agrarian “necessities” and literally plows her own path in her rural sanctuary. Both she and her grandson, then, become beset by bodily malfunction which, at the same time, superimposes on their already divergent emotional make-ups. ‘My body argues with itself,’ he reflects. He tinana rerekē, he hinengaro rerekē tonu.

After his BMX breakdown, the main protagonist - who the reader may well identify with the author Bill Nelson, just as they may assume the volume to be creative non-fiction as much as fictive - returns to the farm to “clean up” prior to its sale. Increasingly, he identifies with his grandmother, herself secured under “care” elsewhere, to the extent of dressing in her clothes and lingerie, while both are also followed by prowling spectator cars at one stage in their respective journeys. He too, is seeking something well away from the encumbrances of mahi, mortgage, marriage, monotony. He in effect becomes his grandmother and the entire final section draws out their proximity of personality as she trudges and then crumbles well away from society, and he – in the concluding lines - makes an existential choice to ‘change from the lane I don’t want to be in to the one I do.’ This ending is open, but the intimation is that our anti-hero is departing the scene of his wife, kids, vocation and heading off somewhere else completely. Perhaps a follow-on will reveal where...?

Tina Makereti cogently articulates this book as expressing ‘a sort of Pākehā whakapapa, or a yearning for it, and a commentary on the ways in which Pākehā reach for connection to place and people...’ I would qualify this statement by pointing out that such a commentary does not apply to all/most Pākehā, and that Nelson concretizes this key aspect, with his recital of the auction of the farm, whereby it is the rapacious and rich land developer who will take over and overtake the property as to construct a myriad of lookalike suburban homes.

In fact, Māori are a noticeable non-existent in the pages of Root Leaf Flower Fruit and it is only, and distinctively, grandmother and grandson who strive to somehow smash the structures of a pervasive Pākehā ethos. An ethos summarised as, ‘They’ll make rational decisions, calculations – investment, profit, extraction, divestment. Inputs and outputs,’ whereby the whenua, the land, is no more than an exploitable object and never venerated as Mother Earth.

It is not easy being dissonant, as Colin Wilson exemplified lifelong himself (The Outsider, 1956), and which Bill Nelson enunciates here so well.

Tēnā koe mō tēnei pukapuka.

Reviewed by Vaughan Rapatahana