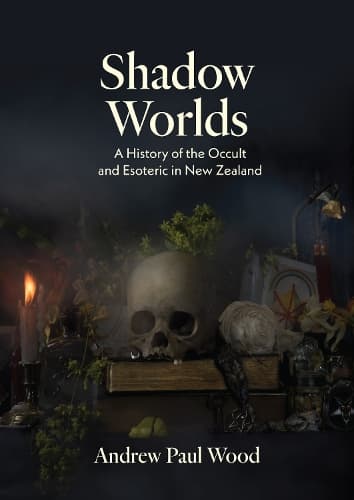

Review: Shadow Worlds: A History of the Occult and Esoteric in New Zealand

Reviewed by Graham Reid

In the 1970s, I went on a very specific book-buying bender and was soon adrift in a confusing confluence of esoteric knowledge and practices: Gurdjieff, J.G. Bennett, Madame Blavatsky, Aleister Crowley, Subud, Rosicrucians, the Kabbalah, Ouspensky…

In Shadow Worlds, teasing apart these threads of Theosophy, The Temple of the Golden Dawn, Anthroposophy and various types of spiritualism is the admirable work of art and cultural historian Andrew Paul Wood.

He excuses himself from discussing Māori spiritual practices and those of the Chinese migrants because their esoteric practices and beliefs would require specialist knowledge and a different cultural context. Although when Māori spirituality was appropriated or bastardised by various outsiders he accounts for those and looks at mākutu and the suppression of tohunga. But he has plenty to explore in the early colonial era and the arcane, esoteric, occult, offshoots and lone wolves living in places like Havelock North, Southland and Hastings.

This is a fascinating, readable book – if complex, have pencil handy -- which illuminates numerous subcultures and belief systems which often found sizeable audiences here. The author accounts for the international rise of many groups – mostly from Britain or the United States – then identifies how, through missionaries or lecture tours, they connected with this country which to many practitioners seemed full of promise as a new world uncoupled from old Europe.

The seemingly staid folks of Christchurch were particularly well disposed to esoteric spiritualism and ideas.

Many prominent New Zealanders appear on these pages as having an interest and sometimes serious involvement with various esoteric groups. Among them 19th century prime minister Sir Harry Atkinson and his wife Annie, tohunga Henry Matthew Stowell (Ngapuhi), Lilian Edger (the first woman in New Zealand along with her sister, Kate) to graduate from a university, Sir Edmund Hillary a member of the highly visible and successful Theosophical Society in the 40s (although after his conquest of Everest he didn't remain one). Thomas Edmonds of “Sure to Rise” bakery fame was a supporter of the Radiant Health movement and the Theosophical Society in Christchurch.

Just as Eastern religions and philosophies appealed to spiritual seekers in the late 1960s, so too esoteric arts took root among intellectuals and truth seekers from the late 19th century and well into the 20th.

‘Theosophy offered a heady cocktail of spiritualism, reincarnation, lost continents and Eastern metaphysics, attractively packaged for Western tastes,’ Wood writes. ‘Its reach was international and connected industrialists, politicians, social reformers and avant-garde artists attracted to the promise of something that transcended Victorian rational materialism and Protestant morality.’

Certainly there were kooks, false prophets, self-promoters and financial opportunists, not to mention the ‘absolute mountebank and charlatan’ Arthur Bentley Worthington (1847-1917) with serial of aliases. A bigamist, fraudster and conman, he was an opportunist in any new and possibly profitable faith. But he also had built the magnificent Temple of Truth in Christchurch in the 1890s (his 12-room mansion was next door) and had a congregation of at least 2000.

Some esoteric groups built impressive places of worship, among them still standing the Theosophy Lodges in Wellington (18 Marion Street) and one on Auckland's Queen Street (now The White House offering adult entertainment). Especially fascinating is the “Vault of the Adepti” inside the Smaragdum Thalasses Temple in Havelock North. Known as Whare Rā (house of the sun) and built in the 1930s, the hidden vault is decorated with Hebrew, Egyptian, astrological and alchemical symbols. Those who had entry allegedly included members of parliament, a couple of governors-general and various respected leaders in their communities.

As the symbols at Whare Rā suggest, a number of these esoteric groups offered an overcooked stew of Greek mythology, Tibetan beliefs, Freemasonry, disturbing theories of racial supremacy, arcane Egyptology and preposterous nonsense (the lost race of Lemurians). But there were also remarkable thinkers and those doing good works in their communities.

Wood wanders off-topic with a brief discussion about the short-lived ohu phenomenon (state sanctioned communes under Norman Kirk's Labour government) and a digression into BLERTA but is more on-point with the philosophical poet Alan Brunton of Red Mole. The myths which grew up around Waitaha -- described by author Barry Brailsford as “an ancient gathering of many people from Europe, Africa, Asia and the Americas . . . founded in the way of peace” – played into post-hippie, New Age thinking in the 1980s.

Chapters have enticing headings: Gomorrah on the Avon, The Women of the Beast, Witchcraft and Neopaganism and The Devil Rides Out (modern Satanism, we have little to worry about). However whatever enlightenment people discovered is unclear as they, for example, climbed the ranks of the Golden Dawn-derived practices at Whare Rā, through levels like the Grade of Geburah to the exalted Ipsissimus state. It must have been more than just getting to wear strange clothes, develop often incomprehensible rituals and maybe boss people around.

A fascinating book about esoteric groups which, despite my voracious reading decades ago, I never knew existed on these shores. Some were downright weird.

Reviewed by Graham Reid