Review: Tauhou

Reviewed by Jane Lowe

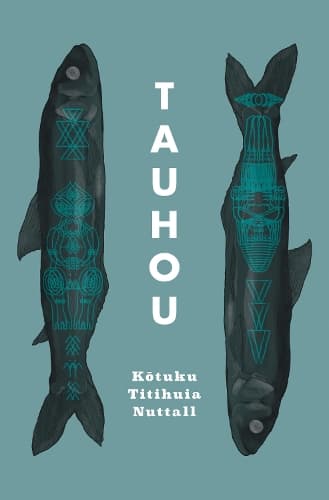

The title Tauhou of Kōtuku Titihuia Nuttall’s deeply magical collection of short stories and vignettes, means stranger or more literally new arrival.

In an imagined world where Aotearoa and Saanich Peninsula, Vancouver are neighbouring islands with a shared history, Nuttall deftly weaves the threads between generations and indigenous cultures together, entwining them as eloquently and as lightly as air. The significance of nature, ‘they say if you want to hide, you must make yourself a raincape of flax,’ each chapter a nod to climate change; the poignancy of trauma and healing, the paralysing loneliness of unrequited love and the mystic past steeped in colonialism is an exploration of the power of knowledge and forgiveness.

I devoured this gorgeous book (the cover art is also done by Nuttall) over a couple of nights, finding myself lost in the beauty and originality that resonates through the pages. Also, (if I’m honest) I fully own that damn-I-wish-I-could’ve-written-this feeling but it didn’t last (long) before I was immediately turning back to the beginning, wanting to linger over Nuttall’s succinct and poetic writing again.

There are layers within layers that play with our senses in a testament to historical trauma and healing, poignant in the telling and honouring of the resilient feminine where the weight a woman carries is fully laid before us. She is fat; she is splayed open on an examination table; she is lost; she is old; her very existence is fraught with danger, still. Yet she watches carefully, noticing, knowing, forging new paths ahead for those behind her.

When re-examined, the recurring repetition of a struggle to breathe, more than anything, sets a disturbing tone: ‘Her father clicked the clips on her jacket and yanked the cords so hard he crushed her chest … She remembers not being able to breathe.’ There is the physical and mental toll of a fractured environment and the subtle signs of addiction, ‘I’ve hung up a picture of my grandmother … Towards the edge of the photo is an empty beer bottle.’ Then there is an underlying shadow of the male, the father. He seems to be yearned for yet somewhat feared, always a shadow, an uncertainty.

In Woody, ‘Very few times, Pa and I go out alone together … He douses the chips in the vinegar so they’re steaming hot and wet. Eating them makes my mouth feel like it’s one big wound.’

In The Sight, ‘She didn’t see another ghost until her father died … He stooped to kiss her forehead and her heart dropped. Then he laughed and was gone.’

In Stones, ‘When Pa returns for the day, I know to be quiet and more reserved … He doesn’t interact with us much, but he likes to take us places and show us things.’

In the section Tauhou it begins: ‘Dear Grandmother, I am writing this song, over and over again, for you. I am a stranger in this place, he tauhou ahau, reintroducing myself to your land.’ Language is forgotten and tested anew, spoken and deliberately not spoken, the linguistics of the te Reo and WSANEC ensuring our characters are fully immersed in their stories, from the horrific reality of the residential schools reverberating long after surviving them, to a taniwha guarding their treasures in a museum.

The circular structure beginning with Daughter and finishing with Mother, and the strong sense of place delivers the stories as if gliding in on the tide, crafted to return to us as nature intended. Nuttall has a gift for ensuring we experience every element of every story, fully immersing us in the moment.

Tauhou is a search for answers, of finding ways to live with the truth. Some of the stories are like fables, others like poetry, and all are a sheer joy to read. A longing for home resonates, a gift for those of us searching for our island also.

Reviewed by Jane Lowe