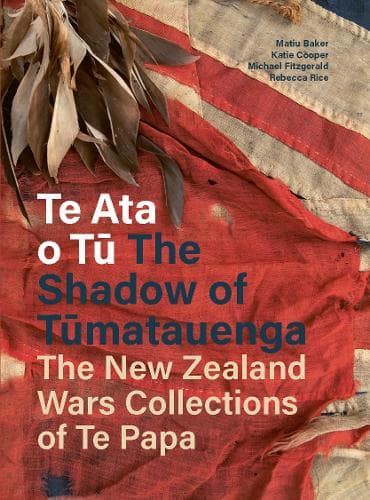

Review — Te Ata o Tu The Shadow of Tumatauenga: The New Zealand Wars Collections of Te Papa

Reviewed by David Veart

This new book based on the New Zealand Wars collection at Te Papa is an important addition to the literature on the subject. Often, books of this kind, driven by collections from museums, carry the echoes of the institutions that formed them. This selection, however, transcends its colonial origins literally in 'The Colonial Museum' creating a powerful narrative using the artefacts woven together with subtle curation and a strong Māori voice, a voice which doesn't simply murmur 'ghostly' echoes from the past but instead speaks truth powerfully into the present.

Described here are objects that relate to the whole period of the 19th-century armed conflict and beyond. From a rusted gun off the Boyd, burnt at Whangaroa in 1809 and the 1870s fortifications of Te Kooti to Mike Smith's chain saw, used to fell the tree on Maungakiekie in 1994, the artefacts create, as the introduction states, 'a library of imperfect memory.'

Hundreds of images support the voices. This is a book about war, so weapons abound, with patu and taiaha sharing space with firearms and swords. While some objects shown are expected there are things that border on the bizarre; a beautiful hei tiki imprisoned in a Pākehā gold setting, encrusted with pearls and diamonds and given by a senior officer to his wife as a wedding anniversary gift. And flags, flags were very much part of this warfare, but given the number and variety shown here, why didn't we look at what we had already tried before attempting the bungled flag referendum?

The images, paintings and photographs create evocative stories by themselves. There is a naive painting by the Messenger sisters of their new home at Ōmata in Taranaki, a neat, two-storeyed colonial house plonked in the middle of a devastated cleared landscape of stumps and logs, Mt Taranaki towering in the background. On the following page is another painting of the Ōmata Stockade perched on an old pā site, Taranaki, again in the background. The Messenger men who built the house also built the stockade, the reality of life on a real frontier.

A major strength of this book is the commentary and associated essays, which link the artefacts to events, groups and individuals to whakapapa. This is a complex story, and it may not always be immediately apparent from the artefacts or popular memory what led to the behaviour of the people involved. For example, one important essay by Monty Soutar examines the meanings of 'kupapa.' Today, it is often casually used to mean 'traitor' as in 'traitor to the Māori cause'; it originally meant 'crouch down'; it later came to mean 'neutral', then 'friendly Māori'. The argument is made that each case must be examined according to the motives of the individuals concerned. A Māori contingent fighting on the government side under the command of its own officers and for its own reasons suggests a different level of self-determination to a group operating under Imperial command.

The emphasis on the place of the participant's individuality continues throughout the book; people's behaviour is often complex and nuanced and extends further than simply the battles. The recovery of the body of 17-year-old Trooper Fred Gill, killed in a skirmish with Te Kooti's forces, is one such example. Captain Gilbert Mair, more famous for his association with the Arawa Flying Column, travelled together with the elderly tohunga Pātara Ngūngūkai through dangerous territory to exhume and prepare the boy's body for return to his grieving mother.

The response of contemporary artists to this history creates some of the most powerful images here. Lawrence Aberhart's photographs of Ripapa Island in Lyttleton Harbour are among the most striking. It was here the men from Parihaka were imprisoned for ploughing up Pākehā farms and rebuilding their own fences after confiscation. I have visited Ripapa, and these images, as seen through the eyes of the prisoners, capture the bleak isolation of the place, while the accompanying image of a mist-wreathed Taranaki hints at the prisoner's remembered homes at Parihaka.

The final essay in this book successfully connects many of the strands. What can we do with the information from this library of imperfect memory?

Puawai Cairns and Ria Hall are both descendants of the iwi of Tauranga Moana, and taking the advice of historian Rongowhakaata Herbert that, each generation needs to restudy and rewrite history for themselves has done just that. The essay 'Te ahi kai po: The fire burning in the darkness and then inheritance of memories' uses the memory of Gate Pa, maps, landscape, an image from the Illustrated London News, the butt end of a broken mere and a series of archived recordings from a local radio station to create revived histories, new memories and a lament. Hall says, 'It is a reminder that we are still here. We are still here and will always be here, regardless of the changing tides.'

I started reading Te Ata o Tū anticipating another 'history in 500 objects' picture book but have found much, much more. As someone with forebears who fought in these wars this book has provided a more complex framework to make sense of this history. As Vincent O'Malley has commented, '...a mature nation needs to own its history, warts and all.' Mature family histories need this, too.

Reviewed by David Veart

Trained as an anthropologist, David Veart worked as a Department of Conservation historian and archaeologist for more than twenty-five years. Veart is author of First Catch Your Weka: A Story of New Zealand Cooking (Auckland University Press, 2008), Digging up the Past: Archaeology for the Young and Curious (Auckland University Press, 2011) and Hello Girls and Boys! A New Zealand Toy Story (Auckland University Press, 2014).