Review: The Back of the Painting: Secrets and stories from art conservation

Reviewed by Peter Carter

Some 33 paintings are included in this collection, with short essays about each one, demonstrating the breadth and depth of Aotearoa New Zealand’s collective art collection. Organised chronologically, the first painting is more than 600 years old while the book closes with a work completed in 2017.

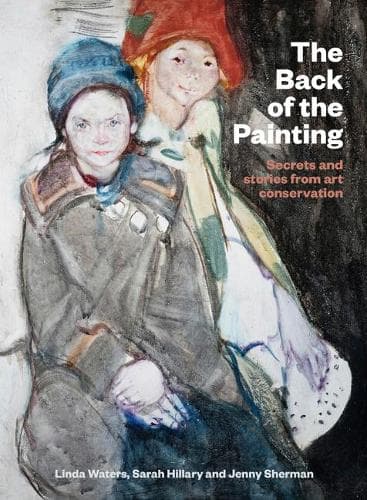

It’s a handsome book with an arresting cover; nicely sized and once I had understood the format, I was referring back from the text to the front image of the particular essay and then to the image of “the back of the painting” to see the points the authors had made. The soft cover made this easy to do. The book is well laid out; the colours and quality of the images are superb.

Of course, it’s not really the backs of the paintings explored here. The Back of the Painting: Secrets and stories from art conservation is an eye-catching title and the information contained in each essay provides an additional lens for looking at the front of each artwork. The essays on each piece are written in a similar style so, I tested myself by dipping in later to see if I could guess which of the three had written a particular piece and found myself succeeding only by making educated guesses as to which painting was held by which institution.

The authors - Linda Waters, Sarah Hillary and Jenny Sherman – are people dedicated and committed to their craft/science who are clearly at the top of their game. They clearly regard paintings as three-dimensional objects, whereas I believe most viewers would regard them as two dimensional.

It’s made clear in the introduction how small the pool of painting conservators is in New Zealand; I was somehow relieved to hear they work collegially. There are six in institutions plus a few others in private practice. The last point brought forward the analogy with what they do to surgery. Pulling things apart, meticulously looking into them and painstakingly putting them back together. Surgery, with plenty of time and no anaesthetic that is. Justin Paton in his How to Look at a Painting talks about a canvas in the hands of conservators, unwrapped from its frame, “laid out for repair like a patient.”

It is an oft-quoted comment that the average time the Mona Lisa is viewed for as a visitor passes through the Louvre is 15 seconds. I recently finished reading Hisham Matar’s A Month in Siena, where the Pulitzer Prize-winning author considers the relationship between art and life by traveling to Siena and spending hours in front of a painting, and then returns, often over a period of years.

These conservators in The Back of the Painting are a leap beyond even that and can spend years looking at their charges, revisiting, caring, and restoring nowadays using techniques that will ensure the minimum of intervention.

The book as a whole had me questioning the lengths and expense the institutions, the curators and the restorers go to to preserve these works. At what stage does the emphasis on preservation overtake that of creation?

Artists no longer necessarily work in freezing garrets but there are many who still suffer for their chosen trade. Much as some of the artists included in this book did, for example Monet. As the authors write, “his finances were in a dire state,” while New Zealand artist Tony Fomison is also mentioned in this regard “…undeterred by incarceration in prison or mental institution nor by his limited means to buy art materials”.

A good non-fiction book for me is one that makes you ask supplementary questions. This book succeeded in that regard; I disappeared down many a rabbit hole. For example, who were the de Beer siblings that as recently as the 1980s donated so many early religiously themed paintings to the Dunedin Public Art Gallery despite not being religious themselves? They were born in Dunedin into the Hallenstein family but spent most of their lives in London and are probably worthy of a biography themselves. The de Beer’s though prompted me to ask, along with other donated work in this book, who are the public collections selected and collected for?

Which brings me to, who this book is written for? To be honest, I’m not entirely sure. It does make you look at artwork that you wouldn’t necessarily look at, though. The earlier works for me are the obvious examples of this; like, I imagine, much of the population, I’d be unlikely to spend much time seeking these out in a gallery.

But I did have my favourites. I love the Frances Hodgkin’s Refugee Children from 1916 used as the jacket image. Hodgkin’s painting induces empathy, of course, but also raises the issue of why we as humans have learnt so little in the last 100 years. Refugees continue to be the subject of artworks. On my next trip to the UK (whenever that will be), I will be visiting Saffron Walden to view Ian Wolter’s Children of Calais, his large bronze, a riff on Auguste Rodin’s Burghers of Calais.

Unknown artist, Portrait of Mrs George Vaile (c.1853). Oil on canvas, 308 x 273 mm.

Collection of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. Bequest of Mr E Earle Vaile, 1956.

The Portrait of Mrs George Vaile, by an unknown artist appeals, too, though it reminded me of the painting Paton discusses in his book of an ancestor that was painted posthumously. The back of Ray Thorburn’s Modular 13, series 2, threw up a pleasant surprise.

In my day job I work with art, quite often we come across canvases that have been painted on the reverse, often this is purely a case of recycling or using what was at hand to undertake an impromptu sketch. Wilhelm Dittmer’s Taketake (Wanganui chief) is an example of both of these. He was only in New Zealand for about seven years and this painting had an unfinished portrait on the reverse so, when the front of the painting was examined, it was discovered that there was a landscape underneath the completed image. (With the quality of contemporary commercially preprepared stretched canvases improving and becoming cheaper, I predict this phenomenon will dwindle over time.)

I read the book contiguously but returned to it many times to flick through. I enjoyed my slightly random ride through 600 years of painting. The longevity of the medium of applying a wet long-lasting substance to what is usually a piece of canvas is in itself remarkable. Also, the lengths these conservators go to, to preserve these works in as close to their original form is laudable. Some of what was discovered on the back of the painting was occasionally a little thin but the additional lens it provides for looking again at the front of the painting made the journey worthwhile.

Reviewed by Peter Carter