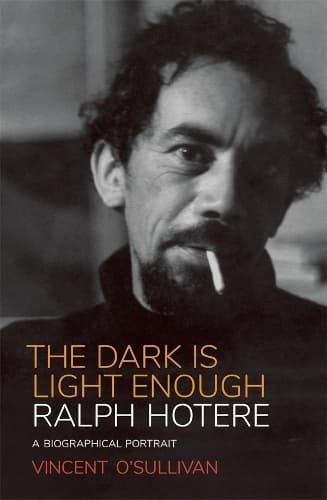

Review: The Dark Is Light Enough: Ralph Hotere - A Biographical Portrait

Reviewed by Matariki Williams

There are two prevailing kōrero associated with the late artist Hone Papita Raukura (Ralph) Hotere (Te Aupōuri, Te Rarawa), firstly the oft-repeated comment of his that he is an artist who is coincidentally also Māori and secondly his notorious reticence when asked to comment on his work. Such is the dominance of these comments in Hotere’s narrative, they tend to determine how his work is interpreted. It is this very reason why Vincent O’Sullivan’s recent biography of Hotere is such a welcome addition to the story of one of Aotearoa’s artistic greats.

With the subtitle of ‘A Biographical Portrait’, The Dark is Light Enough presents a full image of a man who is remembered by friends and whānau as supremely generous and intensely focused in his artistic pursuits. O’Sullivan states his position in writing this biography as an outsider on two points: he is non-Māori and he is not an art historian. However, I do hope O’Sullivan understands that to this Māori, non-art historian reader, his outsider perspective never comes across as being lacking in knowledge. In fact, one example that stands out is his almost forensic approach to presenting the making and exhibiting history Hotere experienced during his time in Europe. This passage is detailed without losing the captivating writing style O’Sullivan deploys.

Perhaps it is precisely because he isn’t an art historian that O’Sullivan understands how important it is to share with readers Hotere’s broader relationship contexts during this time. This international period was one where, yes, Hotere revelled in his access to emerging movements in the visual arts but also maintained existing relationships with Māori and other New Zealanders who were in Europe at that time. One such meeting was with Ruia Morrison, the first Māori and first New Zealand woman to play at Wimbledon. Though this is only a minor reference, I was pleased to read this because of how significant Morrison and her story also are. This mention is indicative of the way in which O’Sullivan treats everyone else in his portrait of Hotere: each person is important, just as they were important to Hotere himself.

But to return to the aforementioned prevailing notions about how Hotere positioned himself as an artist. There is a deftness with which O’Sullivan writes about Hotere and his connection to his whanau; he understands the pull to home that Hotere maintained despite his decision to live so far from the place where he was born and was ultimately laid to rest. This is a pull that many Māori who have moved away from their kāinga understand, that geographical distance isn’t the full story of your connection to home. For an artist whose work is so deeply interrogated, yet not vocally so by Hotere himself, I can imagine the constant querying about the absence of overt Māori visual languages in his artwork would be a source of frustration. I’m hoping that O’Sullivan’s writing puts paid to the tiresome line of enquiry that asks whether his work was Māori or not.

Reading of the way in which grief around significant deaths in Hotere’s whānau, his brother Jack and his parents Ana Maria and Tangirau, impacted his work was incredibly moving. This grief manifested in the Sangro series, including a work which is currently in his sister Charlotte’s care and features a photo of Hotere at Jack’s grave in Europe with his mother’s rosary beads. The image of a whānau circling around each other in such times of grief, including Hotere’s pilgrimage to reconnect the whānau with Jack, is distinctly Māori to me regardless of whatever label others, Hotere or myself decide to put on it. This again is where O’Sullivan’s writing is so potent; it does not need to overtly define Ralph’s identity, the kōrero does this.

If there were one thing that I would like people to take from reading this book, it would be that Hotere is remembered by all who contributed as extremely generous. He loved to work alongside others, noting how wary he was of the word ‘collaboration’ and he always gave. There are countless recollections in the book from friends and whānau who were gifted works by Hotere, heartfelt missives from an artist whose quiet intensity belied a gentle, knowing nature. Judging by the amount of time where he made work in response to events of great personal significance - like the works made in response to deaths and others made to reflect his activist leanings - it is also apparent that he did indeed speak but it is through his work that he did so. Perhaps the most generous move of all was that he didn’t speak on his own work so that we may all find meaning ourselves. Hotere’s evident dislike of boring ‘arty farty crap’ when it came to critical art writing means that there is room for that which he hated but that it can take any manner of forms. One of my favourite anecdotes in the book is of his aunty walking out of an exhibition of his work, dismissing his paintings as random bits of board left in the room. Again, I am grateful that O’Sullivan’s book can hold space for response from well-known art critics as well as those most brutal critics of all, whānau.

It is on this note of generosity that I would like to end because it really should overtake the prevailing kōrero on Ralph Hotere that I open this review with. It is also a helpful segue into discussing that which is conspicuous by their absence, that is, Hotere’s works themselves. There are no reproductions of his work included in the book and I write this just days after the publication in the Sunday Star Times of an article that goes some way to explain just why readers are robbed of this further insight into Hotere. From all that I read of Hotere in this rich portrait, the absence of his work stands in contrast to what it is that he stood for as an artist and as a person. In spite of this, my understanding of an artist whose work I adore has been so enriched because of this beautiful taonga. He mihi aroha ki a koe Vincent, ki te whānau whānui Hotere, ki a koe Andrea, ki te tokomaha o ngā hoa o Rau hoki. Kei te ora tonu a Rau ki roto i a koutou.

Reviewed by Matariki Williams