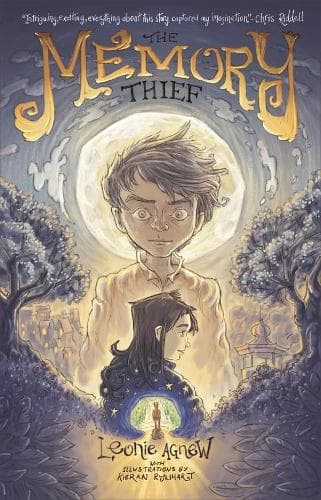

Review: The Memory Thief

Reviewed by Dionne Christian

There are books you read as a child and in the early teen years where characters, ideas or certain imagery stays with you for life. Leonie Agnew’s The Memory Thief is destined to become one of those.

It is a most remarkable book, taking big ideas about life and what it means to be human as the basis for an imaginative, dark but ultimately optimistic story. It will appeal to readers from about nine years up who like intelligent and thought-provoking writing which allows them to reflect on big ideas in their own sweet time.

They might want to read The Memory Thief more than once.

The first time, it will be read quickly because you can’t easily put the book down such is the desire to know what’s going on and what will become of the central characters, Seth and Stella. They’re all the things characters should be: mercurial, sympathetic, memorable, sometimes even unlikeable because of their flaws — and you want to know how things unfold after this chapter of their life finishes.

Seth lives in a park that borders the home of Stella’s grandfather, where the young girl, her even younger brother and mother are living following the sudden death of her father. By day, he’s frozen as a statue of a shepherd boy, but once the sun sets, Seth comes to life – although it’s a sort of half-life he lives - and roams the parkland in search of food. He gets his nourishment not from vegetables or meat, but from human memories. He’s a troll and he can’t leave the park because the iron railings of the park and its gates burn him.

When he meets Stella early one morning, before the sun rises, he realises there is something different about her and becomes increasingly drawn to her. Likewise, Stella is captivated by Seth and a friendship starts. It is threatened when Stella discovers how Seth feeds on memories and determines to use this for her own sad ends.

Seth, who wants only to talk with Stella rather than consume her memories, finds himself in the position of her protector, trying to save her not only from herself but from someone else in the garden who sees her as a threat – and a meal. As he does so, he starts to learn truths about his own existence.

The second time one reads The Memory Thief will be to think more about what Agnew is saying about being human, empathy, forgiveness, and how cleverly she presents these ideas. If memories “kick start” emotions, do we need the bad as well as the good to be fully human? Is a life lived without them truly fulfilling? It sounds complex but Agnew makes it comprehensible and gripping enough that even young readers will be intrigued.

Then, from time to time, you might like to dip into the book to once again enjoy some of the imagery she creates. When Seth first meets Stella, he observes: “Something about this girl reminds me of winter fruit from the glasshouse; fresh juice under a rough orange peel.” When they argue, Seth says: “Suddenly the weight of our argument falls like a snowdrift, burying us in coldness.”

Agnew says The Memory Thief would never have happened without hours spent wandering around the Dunedin Botanic Gardens back in 2013 when she was the University of Otago College of Education/Creative New Zealand Writer in Residence. She has done a virtuoso job of capturing some of the “impossible things” she saw there and making it recognisable to New Zealanders all around Aotearoa.

I have no doubt that the young readers who are enthralled by this, Agnew’s fourth novel, will never look at statues in parks the same way again. Nor will they be so willing, perhaps, to forget the things in life that aren’t so happily ever after.

Finally, Agnew’s imaginative, almost dream-like story is aptly added to by Kieran Rynhart’s illustrations of knotty trees, rambling flowers and sharply pointed park gates that swirl across the beginning of each new chapter. It makes the entire endeavour even more special.

Reviewed by Dionne Christian