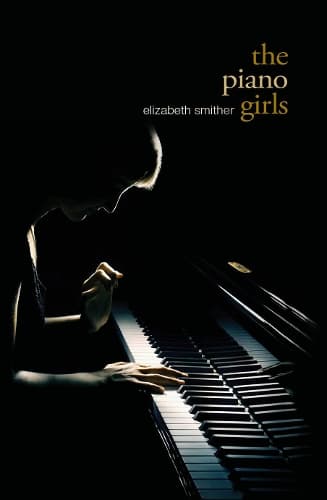

Review: The Piano Girls

Reviewed by Jessie Neilson

Elizabeth Smither is a doyenne of literature in New Zealand, with an output including six short story collections, six novels and 18 collections of poetry. The Piano Girls is a book of 20 short stories, which are mostly delicate vignettes of New Zealanders trying to make the best of their lives.

Some stories display turning points, where an incident or sudden psychological awareness has altered their course, while others describe the unremarkable. Smither's love of the arts runs through her work and is reflected in her characters' preoccupations. This may be a woman on stage in an orchestra recital who, another woman observes, has an "exquisite profile that seemed to have been worn down by music" (The Ten Conductors) or a writer experiencing unusual luxury in an ambassador's residence while at a writers' festival in the tropics (The Shrine of St Anne).

Like Katherine Mansfield's work, Smither's stories portray everyday lives suddenly thrown off kilter by one small act, realisation or betrayal. These characters tend to be female, of varying ages, single or in degrees of relationships. Baking Night is a story of the wisdom that comes with age, where two middle-aged people are tentatively dating, though it becomes clear that they want quite different things. Over the man hangs his shattering divorce, a fact relayed like a memento in a trinket box. The woman, uncomfortable, calms herself with domesticity in the form of baking. Ever the nurturer, the woman shows care through her offerings which may or may not be enough to appease.

In Toothpaste, it is a mother-daughter betrayal where the mother is left as little more than a servant to the young grandchildren while her daughter enjoys a week of overseas luxury. Smither gives insightfulness to some of her characters, while holding it back from others. Here too the grandmother shows wisdom and the acceptance that comes with age. Her thought processes are emotion-ridden and impulsive at first, then turn from a "volcanic kind of cocktail" to a flat deflation, where she decides to put aside the hurt, "the consciously given, the unconsciously given," knowing that everything will pass.

Another strong impression that comes through Smither's work is of our essential aloneness. Even if in a loving relationship, we stand alone in our body and mind, as both slowly deteriorate. We witness a woman whose body has let her down through a skin condition in The House of Skin. She has spots snaking down her arms and "tiny black corpses" decorate the bed sheets. Smither portrays a person's frailty, in this case, of a woman who swings between optimism and pessimism as she juggles twin roles to herself of nurse and patient.

A particularly moving piece is Scottie, where a former society hostess is now a wizened old woman, serving up third-rate meals for her appreciative young male neighbours. These days Scottie wakes up slowly, moving her arms like the wings of a bird, warming them up so they can function for the day. There is nothing glamorous about ageing, Smither demonstrates.

She portrays her characters gently and subtly, where the reader can feel growing empathy towards individuals as they fight off the degradation that comes with age. She notices the small details: the shifting interactions between people, from infatuation to hostility; the putting on of a brave face; the posturing, behind which hides shattered selves.

This collection is fresh in its variety of personalities and narrative trajectories. It also displays a great range of settings in which to place the human condition, sometimes when the going is good but, more often, where people are facing challenges from outside or are struggling to ward off their own vulnerabilities.

Reviewed by Jessie Neilson