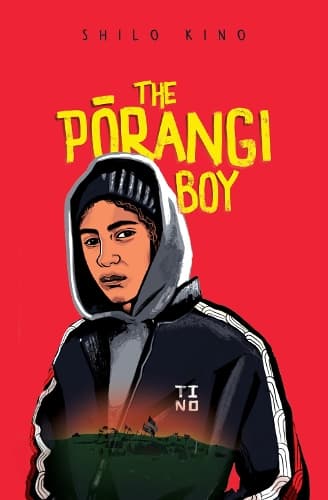

Review: The Pōrangi Boy

Reviewed by TK Roxborogh

Niko Te Kainga-mataa, uri of Hongi Hika, a Ngā Puhi chief, takes up the challenge to protect the natural habitat of Taukere, the local and sacred taniwha, against those who would build a prison. People willing to stand up against the wrong are usually vilified, bullied, made fun of. They are called crazy, weirdos, strange. Society is uncomfortable with individuals and small groups standing up against those in power – especially against those who use their power for selfish gains.

In The Pōrangi Boy, this is true for Niko’s grandfather (Koro) as it is for Niko himself – bullied at school (lead by his cousin) and neglected by his parents (his dad is not on the scene and his mother isn’t really either – the suggestion that her ‘sickness’ is drugs or alcohol fueled). The writing is a delight to read. Here’s an example of an early interaction between Niko and friend Wai:

‘Is that your mum?’ Wai’s holding an old black-and-white photo in her hands.

‘Yeah.’

‘Your mum was pretty as! Not saying she isn’t now… she just looks old, aye. How come she never comes out of the house? Haven’t seen Aunty in forever.’

‘Why don’t you ask her?’

‘Woah, angus. Sorry I asked.’

‘Well, how come your dad’s locked up?’

Her eyes stay on the photos. ‘The effects of colonization.’

‘Aye? Do you even know what that means?’

‘Nah.’ We both crack up.

‘That’s what my dad says. That the Pākehā colonized us, and now our people are all locked up. Anyway, he’s coming out next year! He’s got a flash job already with my uncle driving trucks, cool aye? Do you know your dad?’

‘Nah.’

‘Did he do a runner?’

‘Ask my mum.’

‘Is he a Pākehā?’

‘I dunno.’

‘Don’t you wanna know who your dad is?’

‘My koro was my dad.’

Words are not wasted and the sharp eye of observation is evident with each carefully chosen sentence. Through this matter-of-fact conversation, the reader is able to learn and understand the details of Niko’s world - all its struggles and challenges – but it communicates without being maudlin or preachy. The lives are what they are and, even though we might giggle alongside them as we eavesdrop on their conversation, we are moved by the stark truth of their circumstances.

There are many things I appreciated about this book: the fluidity of the writing, the authenticity of the dialogue (and how familiar the sounds were to me – I’d forgotten how we used to all say,‘Far’ and ‘Aye?’ to each other as kids growing up in Northland), the credible characterisation, the interesting plot structure (Before and After as chapter headings for the first half of the book) to establish scenario and the motivations of characters.

I finished reading The Pōrangi Boy at the same time as watching the televised storming of the US Capitol. The contrast of the narratives could not have been more clear to me: in the novel, a small group of (brown) people trying to protect a sacred site from being decimated by a new prison (the purpose of the construction in and of itself symbolic of the values held by those in authority) became even more honourable and important to me when compared to the murderous mob of right-wing, white supremacist Trump supporters who attempted to subvert the legal process of confirming the US election results.

Huia Publishers deserve the accolades they are receiving from readers and booksellers about their publications – the books they are producing are worthy of the high praise. But author Shilo Kino deserves huge congratulations for producing a fantastic read. The book will find its way into the hands of those who need to read it (because it is celebrating their world) and those who should read it (anyone who needs to walk in the shoes of kids like Niko and Wai). It is a novel that would be wonderful for a class study – a teacher could focus on the writing style (use of present tense, dialogue), subject matter (protesting, poverty, whānau, bullying, relationships/friendship), and themes (being a leader, the importance of conservation and tikanga, what it means to be a real warrior).

I am so glad that Kino has used her incredible skill as a journalist to write fiction. The children of Aotearoa deserve the treat of her books.

Reviewed by TK Roxborogh