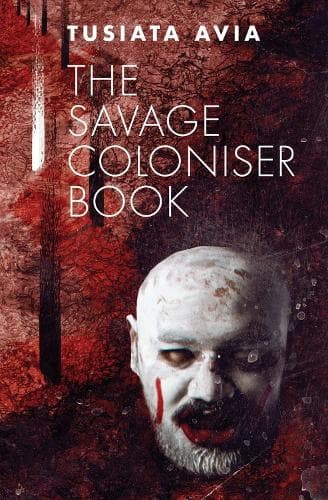

The Savage Coloniser Book

Reviewed by Leilani Tamu

With exquisite poise in every aspect of its poetic execution, The Savage Coloniser Book is a torch that sets alight hundreds of years of racist kindling that has been gathering under the oppressive yolk of colonisation … and lets it burn.

This book is a reckoning. It is the reckoning that those of us indigenous to Te Moana nui a Kiwa have long been waiting for. It is a book that, on the one hand, brings together a collective and shared agenda: fighting for justice and calling out racism and on the other, speaks to a way of knowing that is ancient, complex and clearly articulated in a way that only great indigenous artists gifted with the sacred baskets of knowledge can.

Building on the foundations of her three earlier acclaimed poetry collections - Wild Dogs Under My Skirt (2004), Bloodclot (2009), Fale Aitu | Spirit House (2016) – in The Savage Coloniser Book Tusiata Avia rises to her zenith. For the most part, the poems in this collection are fiery nifo oti (Samoan ceremonial death knives) crafted by Avia with one target in mind: the jugular of White Oppression.

Kneel like a prayer full of lynching

Behold the power of God

Crushing the head of a black man

This is my God-given white

(from the poem BLM)

Backed by the Samoan god of earthquakes, Mafui’e, who although only mentioned once is ever-present in the vā (relational space) of this text, Avia sharpens each blade and wields words with spiritual prowess until they blister in our mouths. As we walk with Avia through the blaze of her poetic wrath, as readers we not only endure the humiliation and anger of being forced to swallow the daily ‘poison pellets’ of racism, but also feel the pain of the rolling undercurrents created by the seizures Avia herself has had to survive since being diagnosed with ma’i maliu (epilepsy, death sickness).

Pain and grief therefore are ever-present in this book and like precious ‘ie tōga (Samoan fine mats) are threaded so finely throughout the collection that at times the references to sorrow are almost indiscernable. Yet in the deafening sorrowful silence that sits before, after and underneath the poems ‘Massacre’, ‘Man in a wheelchair’ and ‘Prayer’, the alagaupu (Samoan proverb) that opens the collection rings clear and true:

E logo le tuli o le tātā

The deaf hear when they are reminded

I’m not going to lie: The Savage Coloniser Book is not for the faint-hearted. If you suffer from even the teensy-ist bit of White Fragility, hold on tight because these poems aren’t written to make you feel comfortable, they are written to hold you to account. In contrast, for those of who have had to learn ‘How to be in a room full of white people’ (my favourite poem in the collection) this book is healing medicine.