Review: Thief, Convict, Pirate, Wife: The Many Histories of Charlotte Badger

Reviewed by Dionne Christian

Pity the poor historian stuck in the archives trying to piece together the life of Charlotte Badger. Given what’s been previously written about Charlotte, you’d think there would be a trail of paperwork a nautical mile long but no. Instead, there’s been a lively mix of newspaper stories, mentions in other history books, fantastical paintings, a play or two and Charlotte’s Kitchen, a Paihia restaurant named in her honour with a fabulous but highly stylised depiction of her.

It's contributed to lifting Charlotte from relative obscurity to legendary status as Australia’s first female pirate – turns out to be wrong – and the first Pākehā women to live in Aotearoa. While exaggerating her escapades may make for rip-roaring adventure yarns, it does not make for truthful history. Furthermore, it risks doing Charlotte a disservice by not giving context to her life against the background of the unfair, biased and downright hard-scrabble times in which she lived, committed crimes and, no doubt, toiled in.

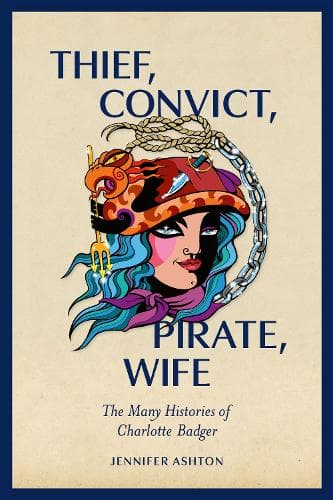

Thief, Convict, Pirate, Wife: The Many Histories of Charlotte Badger is historian Jennifer Ashton’s determined attempt to unravel who Charlotte really was rather than blithely accepting and repeating what has already been written. Ashton could have concluded that there wasn’t enough information to put flesh on Charlotte’s bones and left it at that. (For example, while we know Charlotte was born in 1778, there’s no record of where and when she died so her life can’t even be ‘neatly bookended.’)

But instead of abandoning the project, Ashton has ultimately produced a deeper cultural history which shows how history itself, and historical figures like Charlotte, are made and remade across time by journalists and historians, painters and playwrights depending on the concerns of their day. Even by stripping away some of the ‘myth-history’ built up around Charlotte, Ashton succeeds in showing why she remains remarkable and interesting – a true survivor, if nothing else – who can tell us more about her own times as well as ours.

It means this is not a book for those who prefer their history ‘lite’ or who look for certainty and definitive answers from the past. As Ashton writes: “This is a story of doubt. It is a story of people who left little trace… There are no writings to pore over; no monuments to gaze at; no perfectly preserved homes to visit. We will never see their faces; we cannot hear the sound of their voices. In other words, they were like most of those who inhabit the past.”

It’s a careful and revealing piece of historical detective work, a story about stories themselves. Plenty of those exist about Charlotte. A teenaged thief from Worcester, England, she was sentenced to death for a minor crime only, four years in prison later, to have the sentence commuted to transportation to the burgeoning New South Wales penal colony. Charlotte survived what would have been a grueling sea voyage only to disappear into the morass of women who were expected to be a civilising force in a frontier society.

She next reappears in the historical record five years later in 1806 onboard the Venus, a vessel chartered by the colonial government to deliver food to Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania), as part of a mutiny. As Ashton points out, we can only speculate about the motives for the mutiny and Charlotte’s role, whatever it was, grew exponentially with each retelling. The mutineers sailed across the Tasman and reached the Bay of Islands, where Charlotte left the Venus – its fate remains unknown – and became the first white woman resident in Aotearoa, possibly the wife of a Rangatira.

In this, she was a cultural emissary much like the other convicts, runaways, sailors and soldiers, governors and missionaries that Ashton describes as she constructs a picture of the maritime and imperial world circa the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It successfully shows this world as a good deal more mobile, diverse, dangerous and unknowable than we might imagine.

There was talk that Charlotte made her way, via Tonga, to North America where she was lost to us. However, Charlotte returned, via Norfolk Island, to Sydney where she married and presumably lived out her days. That’s not certain, though, as there is no record of her death.

Fascinating and frustrating, this an insightful historical biograph that reveals as much about how we make our histories as it does about Charlotte Badger.

Reviewed by Dionne Christian