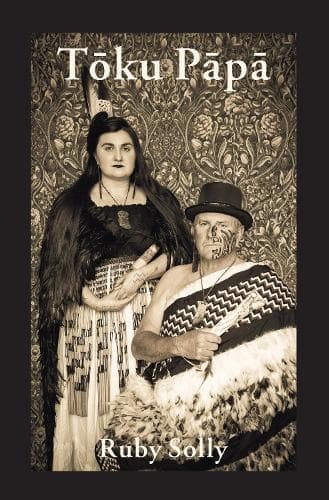

Review: Tōku Pāpā

Reviewed by Arihia Latham

I remember the day Ruby called me in 2019 and said, “I have a feeling we might be more closely related than we thought.” Finding a cousin who already exists in my writing life has been solid. Her Nana and my Pāpā are first cousins, her Pāpā and I are second cousins, Ruby and I are second cousins, once removed. We were once removed, and now we have found each other, not a second too soon. When I was hapū with my third child I woke from a dream to the call of the Ruru out of my suburban-not-where-Ruru-live-house. I knew then that the pēpi inside me was to be named after our tupuna, our great great Tāua Koukou. The thing is, she was talking to Ruby too, she was weaving us together through the poetry of birds.

Her call creeps through my window

and into my dream

I am someone else

a long time ago

I wake in the dream to hear

Koukou, koukou.

Then I wake into myself and hear again

Koukou, koukou

We have a tupuna named after the morepork’s cry.

I think of how she must have been born singing.

Ruby’s book is full of lyrical archeology. She unearths words and feelings buried in the bones of our whakapapa. I don’t know how you, a stranger to us, will read this book. I can only tell you how it is, as whānauka to consume these words like she has translated the braille of clay on rock from our tupuna.

This is a book to her Pāpā but it is like a pūtōrino playing to him down the motu, saying, “Are you listening to me, are you listening to the past? Take me home, show me the way through to the future.” She leaves me with a sense of strength and vulnerability I know in my bones, the flash in our eye that says, “look at how I had to fix myself in dreams and promises inside the rivers of thoughts in my mind.”

Ruby’s poetry is the story of the unwinding, the difficulty, the restructuring and the settling:

This is a soundless space

before the sounds are born.

The kōauau calling the gods back in.

The porotiti pulling sickness from flesh,

singing a darker world into being.

The trees let leaves fall.

The birds moult feathers.

There is no one here to see the difference

between stem and spine.

I wake to two new worlds.

Past and present compressed

into each cell

unwinding in me

fraying out like a rope.

The syntax of Ruby’s language is vibrant, it surprises me that she can describe something known in such a unique way. I feel like it should have been described that way always. But who could think to compare ballet to machetes or to speak of rivers hidden by concrete with, “I hear it rage under our atmosphere.” She writes, “my bones push at my skin, trying to sing themselves home,” and I feel it. Once you read these things, they are formed, they are here in the world and they make sense. It’s like a new language that you realise you already know.

In the aftermath

you are sleeping behind the sun

as the wind stirs feathers and grass

into frenzies.

I follow your trail,

pluck feathers from the air,

shape my arms into wings.

I climb the tallest tree

and jump

hoping to fly

hoping to fall.

Our tupuna Koukou is always calling to us. I know that she is watching Ruby climb this tree of words and I have no doubt that she will exhale deeply on the wind to ensure that she flies.

Reviewed by Arihia Latham