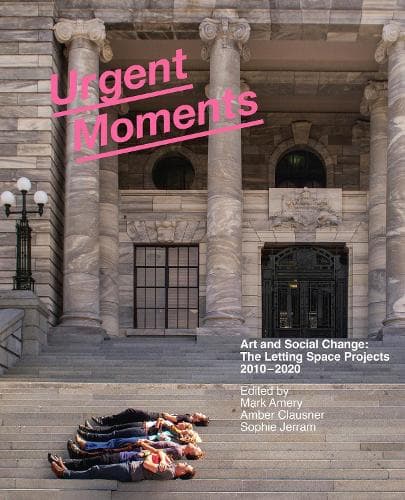

Review: Urgent Moments - Art and social change: The Letting Space projects 2010–2020

Reviewed by Graham Reid

Much contemporary art aiming for controversy has a short shelf-life. It takes the grand gesture – Damien Hirst's shark in formaldehyde or diamond-encrusted skull – to really get people talking.

Who now remembers the early 90s controversy around Virgin in a Condom – a meagre idea poorly executed - let alone the artist's name? Sex and Catholicism: the clickbait of its time.

But controversy is good for the art business which rarely gets public attention, even if it's used to raise the wearisome and threadbare question, “What is art?”, often coming from artists who – in their refusal or inability to explain their work – leave it to curators, gallery owners or cheerleaders to essay it into existence and load it with meaning.

Installation or conceptual art faces special problems: by its very nature it's often here and gone.

Of course, there's nothing in the contract which says art needs to be permanent but once it’s gone social media chatter moves on, headlines (if there have been any) turn to sepia and . . . what's left? That's why this well designed, illustrated book of essays and comment is important.

The subject is the Letting Space Projects – offices, rooms and outdoor spaces taken over by conceptual artists – and its prime movers Mark Amery and Sophie Jerram's self-imposed challenge to “transform the relationship between artists, the public and their environments to enable social change.” That's a big ask, but if art can't always effect social change it can prepare its audience for questioning and dissent.

If not all Letting Space projects succeeded, at their best they challenged convention and forced questions - not just about art but social structures, economics, commerce and accepted practices - into the public domain. One of the most quietly goading, witty and controversial was Tao Wells' Beneficiaries Office staged in Wellington in late 2010. Wells argued that, among other things, the unemployed use up fewer resources so set himself up an empty office on Manners Street as a PR firm, The Wells Group.

Tao Wells' Beneficiaries Office.

On the benefit, he was gainfully unemployed and as such became a target of media outrage – taxpayers' money for this? – which fed the worst tendencies of the media and commentators. The NZ Listener railed against him in a full page editorial, the Dominion Post claimed – wrongly - he'd been given a $40,000 Creative New Zealand grant. Shades of the wilfully uninformed, rabble-rousing Paul Holmes banging on about et.al at the 2005 Venice Biennale.

Throughout Wells let the discussion range into questions about work, welfare, the media, consultants, the arts . . .

Barry Thomas overstated the project in Artbash, calling it “a powerful moment in art history” but through conversation and argument it engaged people beyond the arts community. Mission accomplished.

Equally important was Free Store by Kim Paton earlier that same year: a store in which donated produce from Progressive Enterprises and local retailers was made available to those Paton trusted to be there because they needed to be. Again questions raised about capitalism, consumerism, waste, civil and corporate responsibility. It made Campbell Live.

Not everything here is so serious: the frivolous proposal for tortoises on a bed of grass in a retail space - their shells decorated like subatomic particles – might have been amusing. Although probably not for the creatures themselves.

But from the Porirua People's Library and other exciting, site-specific Letting Space Projects in that suburb to Vanessa Crowe's Moodbank in Auckland's Wynyard Quarter (emotional life vs capitalism), murals and Siv B. Fjaerestad's painted fields, these were art projects which mostly appeared, provoked and then left.

Did they “transform the relationship between artists, the public and their environments to enable social change”? Some, others perhaps not much. If at all.

But the importance of them, and this book, is that they happened and deserve to be recorded.

The lengthy section on the post-quake TEZA (Transitional Economic Zone of Aotearoa) work in New Brighton – a sincere and mostly successful attempt at community engagement – is especially valuable and still relevant.

Yes, on these pages practitioners and their champions mostly talk amongst themselves, much of the commentary coming from the Letting Space website which rarely challenges but rather interprets and expands on the interactions. And sometimes, but not that often, there's the jargon of the art world: space or ideologies interrogated, interventions and interfaces.

But this is a lively, readable, thought-provoking and occasionally funny account of the central and important subject matter: Art that doesn't just “raise questions” but frequently posits answers.

The images, installations and events may be gone - you'd love to have seen the colourful pathway of second-hand clothes rolled out along Wellington streets by Lebanese artists Rana Haddad and Pascal Hachem – but they, and the ideas brought to light, are preserved in these pages, ready to re-emerge at any time.

As documentary photographer and Ilam lecturer Tim J. Veling advised the artists at the New Brighton project, “Echoes of conversation need to continue”.

Reviewed by Graham Reid