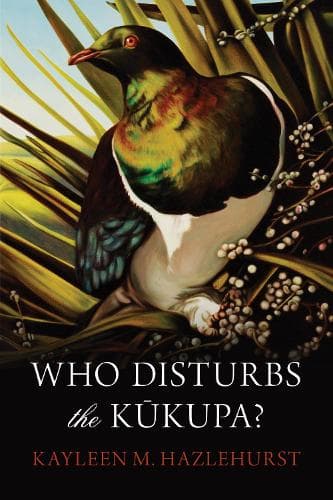

Review: Who Disturbs the Kūkupa?

Reviewed by David Hill

April, 1941: My Uncle Hughie was in Greece along with other New Zealand personnel when Operation Marita brought German forces storming into the country, shoving Allied troops into precipitate retreat. Near the end of that month, he was one of the 57,000 evacuated, just ahead of triumphant Axis armies. He was profoundly unimpressed by the whole affair. “A bloody shambles,” he called it, decades later. Actually, he used a more pungent adjective.

Hughie was sent to Crete. A few weeks later, he and a group of other New Zealanders were escorting King George of Greece, Prince Paul, the Greek PM and other dignitaries across the island's mountains to the south coast, for another evacuation. It was like walking from Napier to Taupo, he told me, except with bombs and shells landing around you. As a reward for getting the VIPs to safety, Hughie and his mates were promised leave in New York (sic). It didn't happen and he was unimpressed by that, too.

That defeat – which it was – in mainland Greece and subsequent events are the background and foreground for Kayleen Hazlehurst's second novel. A soldier from the 28th Māori Battalion is separated from his unit and has to escape through a country of frightened refugees and apparently unstoppable invaders. Like my uncle, Sonny makes it to Crete.

But he isn't among the lucky evacuees. Instead, he joins one of the partisan groups striking at Germans forces from the gauntly beautiful White Mountains. When he does finally make it off the island, it's to Egypt, and then, ominously, to Monte Cassino. Meanwhile, back in a Northland that's at peace but not peaceful, fiancée Atarangi waits and worries.

The story is set with chants, karakia, proverbs, symbols – several involving the eponymous kūkupa, the native wood pigeon. It begins in 1939, as Michael Savage and Peter Fraser try to brace the country for war, and the Niagara is sunk off Bream Head. It ends eight years later, with commemoration services for the dead, and a future where scientists have ‘learned how to tear a hole in the cloak of the Universe.’

There's no shortage of action, at sea, in a monastery, on a plateau where nightingales sing. We get escape by rowboat; enemy patrols and devious spies; near-starvation in a bare, beleaguered land. Back home, families attend church, talk of visions, fear news of death or disappearance among their men overseas. You might wish for more variety of pace occasionally, but vivid scenes stand out: a ‘seal wife;’ a landing craft packed with ragtag escapees; a mountain cave in winter.

Hazlehurst's research is meticulous – and respectful; she's consulted the journals, letters, whanau of Māori Battalion fighters. Credit to her for the thoroughness and care. Meticulous research doesn't always mean a memorable narrative, and the weaknesses of Who Disturbs are ones of inclusion rather than omission. The author is understandably fascinated and often moved by what she's found; she wants readers to share her feelings. The result is a plot crammed with details that are individually striking but cumulatively sometimes clogging.

The writing is vigorous if adjectival; Hazlehurst does tell us quite a lot, rather than letting her people and their actions show us. But Sonny's transition from impetuous boy to resourceful, compassionate adult is engaging, while Atarangi's narrative arc should put a lump in your throat.

It's a courageous novel that tries for historical sweep, imbues the everyday with the mythical. Its reach may sometimes exceed its grasp but it's always faithful to its people and the worlds to which they belong.

Reviewed by David Hill