Review: Sight Lines, by Kirsty Baker

Reviewed by Jade Kake

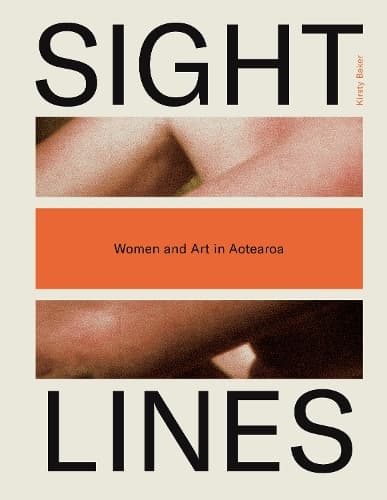

Kirsty Baker, an art historian, curator and writer based in Te Whanganui-a-Tara of English descent, has woven together a remarkable new book on women and art in Aotearoa. Sight Lines: Women and Art in Aotearoa is a hefty 444-page work with 150 striking images.

The book is structured chronologically by birth date of each artist and includes a good cross-section of Aotearoa artists working across a wide range of mediums, including painting, photography, digital/multimedia, ceramics/sculpture, and installation, working as both individuals and within collectives. The design of the book favours block colours in an olive and highlighter orange palette, the colours alternatively identifying chapters authored by Kirsty Baker (the principal author) and contributing authors (which include eight art writers, many of whom are also artists).

The title references the Mataaho of both Maureen Landers’ work (Mataaho / Sight Lines, installation at Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, 1993, mixed media, dimensions variable) and the Mataaho collective, named in reference to or as homage to this work. In this context, ‘mata’ refers to ‘sight’ and ‘aho’ refers to lines. The title of the book is fitting, touching on the many interconnecting threads of the book, both literally and figuratively – through the intergenerational transfer of knowledge, and the tuakana-teina relationships formed between many of the artists. The title also refers, perhaps, to the, at times, uneasy tension between Pākehā settler-colonialism and Māori resistance and moves towards decolonisation.

The word ‘women’ is considered in the most expansive definition of the word – with some discussion presented on its inherent limitations – with trans artists included unselfconsciously in the line-up. These artists are presented in the book firstly, as artists who are women, and defined by their queerness or their transness only insomuch as their work addresses those themes. Aotearoa is permitted to stand alone, without the addendum of the colonial moniker.

The book begins with a stunning treatise on Wahine Māori and adornment, He toi rākau, written by Ngarino Ellis, which deserves special mention. The essay, right from the outset, challenges our view on wāhine Māori (or ourselves as wāhine Māori, depending on our positionality), what we take for granted as ‘traditional’ concepts of beauty and adornment vs what has been purposely distorted and internalised through colonisation. The essay purposely sharpens our lens and awareness, priming us for the chapters that follow and preparing us to read critically, bringing careful consideration of context, our own positionality, and the cultural and social forces that shape our world to the forefront of our reading.

Kirsty Baker, the principal author, is careful to identify and declare her positionality (her whakapapa is from England via Scotland), and it is from this position that a genuinely relational inspection of Women and Art in Aotearoa is possible. Sight Lines features a wide range of contributors, and it is this genuine polyphony of voices that defines the book. Baker, in this sense, is a weaver, stitching together the contributions of others into a cohesive whole.

Weaving – typically, but not exclusively, an artform within the domain wāhine Māori – has prominence in the book, with Baker and other contributors resisting the easy binary of traditional and contemporary. Instead, ‘traditional’ weavers, such as Rangimārie Hetet and her daughter Diggeress Te Kanawa, as well as the unnamed makers featured in the chapter on Whatu kākahu are given space to develop their craft and recognised for their bold innovation within a clear set of parameters, whilst contemporary artists, such as Maureen Landers and the Mataaho collective, are permitted to draw on woven techniques and reinterpret through space and site-specific installations.

Critical interrogation of the work of Pākehā artists is included, notably Rita Angus (Rutu, 1951, oil on canvas, 715 x 561mm) and Margaret Matilda White (self-portrait, 1890-1910, silver gelatin dry plate glass negative, 164 x 120mm). Baker is careful to both identify precisely what is problematic about these works from a contemporary viewpoint, whilst also being sure to contextualise and enable the reader to understand these works within their own time and place. The message being, even though these discussions may be difficult, we should not shy away from naming and critiquing Pākehā art, which operates indivisible from settler-colonialism, racism, and white supremacy. Baker also features Pākehā artists who have worked in close collaboration with Māori communities, such as Fiona Clark, whose work offers possibilities for Pākehā artists to consider their roles and responsibilities as tangata tiriti – should they choose to embrace being identified as such.

The book also features a particularly noteworthy essay on Elizabeth Ellis and Mere Lodge, with the contributing author (Chloe Cull) noting her own contemporary assumptions and judgements that she brought to a retrospective consideration of the artistic careers of these two early Māori women artists, as well as the inherently hopeful, but clear eyed, perspectives of Ellis and Lodge themselves. The interviews and accompanying self-referential analysis reminds us – a repeated motif throughout the book – to bring both our contemporary understanding of societal expectations as well as a genuine attempt to understand context to our retrospective reading, as well as a generosity of spirit that allows women agency and dignity.

This book is a taonga, and my criticisms are very minor. A book of this nature can never claim to be truly definitive (Baker carefully avoids that trap by stating upfront the impossibility of such a proposition), or please everyone. With that said, I would have loved to have seen contemporary artists such as Raukura Turei, Nikau Hindin and the Kauae Raro Collective, who work extensively with natural pigments, featured in the book. I would also have liked to have seen some visual material accompanying the chapter on Janet Lilo.

The titular many threads are evident and interwoven throughout the book, and the criticality and critical awareness of the social, political and cultural context of the artists and their works represented within the book is much needed (and seldom witnessed) within Aotearoa art writing. An important new text.

Reviewed by Jade Kake